Common People, a pigeon narrator, and bank robbery. Just some of my July reading highlights…

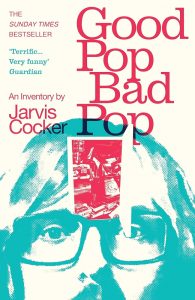

Jarvis Cocker – Good Pop Bad Pop (2022)

After going to see Pulp for the first time (I will remember the first time) last month at a simply brilliant gig, I’ve had them playing more or less non-stop since. So, what better way to find out more?

This book gives an expectedly eccentric look at how Jarvis Cocker started the group, telling the story of his growing up – through the medium of sorting the contents of his loft. With each item – from schoolbooks to sweets, broken glasses to keyboards – there’s a well-told tale.

The book focuses very much on Jarvis’ early years, when Pulp’s fame wasn’t Pyramid Stage – going as far as his enrolment in St Martin’s College…do you recall?

It’s well worth reading as a physical book rather than an e-book – the formatting and pictures are an absolute delight.

Bob Mortimer – The Hotel Avocado (2024)

The sequel to The Satsuma Complex is just as delightful, with the main characters returning for yet another silly and surreal crime plot.

Mortimer’s humour shines through with throwaway sentences in the middle of an otherwise serious conversation between characters, and the protagonist Gary soliciting advice from a squirrel. Yet, the characters are largely believable and do have depth, particularly with the chapters switching perspectives.

It won’t be everyone’s cup of tea, and it probably makes even less sense if you haven’t read The Satsuma Complex first – but it’s a joyful way to spend a few hours chuckling at blackmail, mince, and pigeons. I doubt there’ll be legs in the characters for a third in the series, but who knows with Bob?!

Gary Stevenson – The Trading Game (2024)

Stevenson has rapidly risen to prominence as an economist with TV appearances calling for a wealth tax, and his memoir tracks his journey from school expulsion through to becoming a burnt-out and disillusioned trader.

Most of the book is devoted to Stevenson’s attempt to leave his bank, who first recruited him out of university through a card game competition – and whose employees are largely shown to behave, well, about how you’d expect.

After a moment of enlightenment that betting against the economy would be profitable for him and the bank, Stevenson rises to become one of the leading traders and describes claiming his bonus as a ‘bank robbery’ – though, the bonus is paid in slow instalments and used as leverage to keep him in post.

Stevenson’s deep knowledge and passion about the economy and wealth inequality – as well as anger over how the sector operates – does shine through in moments here.

Honourable mention

Elliot Sweeney – We Don’t Use Words Like “Crazy” (2025) – is a powerful memoir from the frontline of mental health treatment in the UK, which shows the failures of a shockingly underfunded and misunderstood system. There’s also a neat balance of humour, and it’s hard not to be touched by Sweeney’s evident compassion and dedication to the role.